Why the Art World Is Embracing Craft

Artsy_“I’d give anything in the world if that little girl with the red hair would come over and sit with me.” That’s Charlie Brown, in the first mention of his schoolyard crush, published in 1961. That is about the same time the studio craft movement conceived its longing for art-world recognition. Inspired by the revolutionary works of ceramist Peter Voulkos, weaver Lenore Tawney, and furniture-maker Wendell Castle, craftspeople across America embraced a novel idea: What if they put their skills to sculptural, rather than functional, purposes?

They did their best, but the art world paid scant attention. Partly, it was bad timing. Craftspeople discovered modernist expressionism just as the avant garde was moving into conceptual art. Partly, it was old-fashioned disciplinary disdain, artisans being kept in their place. And partly, it was a gender issue, as crafts were an unusually welcome place for women’s creativity. Whatever the reasons—and they were complicated—the craft world’s hope for a broader embrace went unrequited.

All good metaphors must come to an end, though. Charlie Brown got his first kiss in a 1977 television special. It took craft quite a bit longer, but look around today, and you would hardly know that a hierarchy had ever existed. Things changed first for ceramics, with a bellwether exhibition titled “Makers and Modelers: Works in Ceramic” at Gladstone Gallery, in 2007. Hot on its heels was “Dirt on Delight: Impulses That Form Clay,” curated by Ingrid Schaffner and Jenelle Porter at the ICA Philadelphia. And then, suddenly, ceramics seemed to be everywhere: at the fairs, in the galleries, and on auction blocks. Voulkos underwent a dramatic reappraisal—in 2017, his monumental sculpture Rondena (1958) smashed his auction record when it sold for $915,000, or nearly double its high estimate, at a Phillips evening sale—as did others in his circle, like Ken Price and John Mason (the latter is the subject of a new solo show at Gagosian).

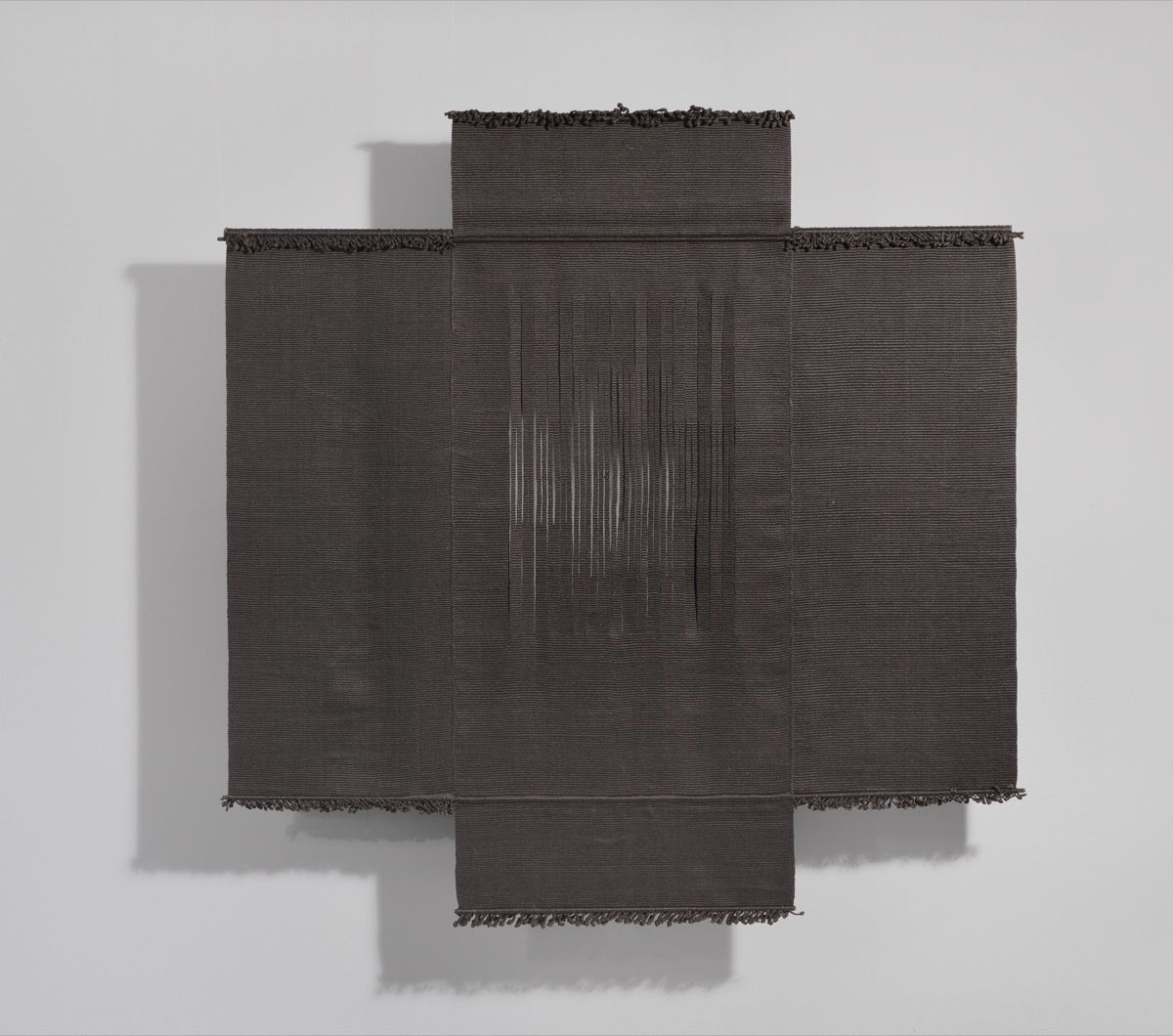

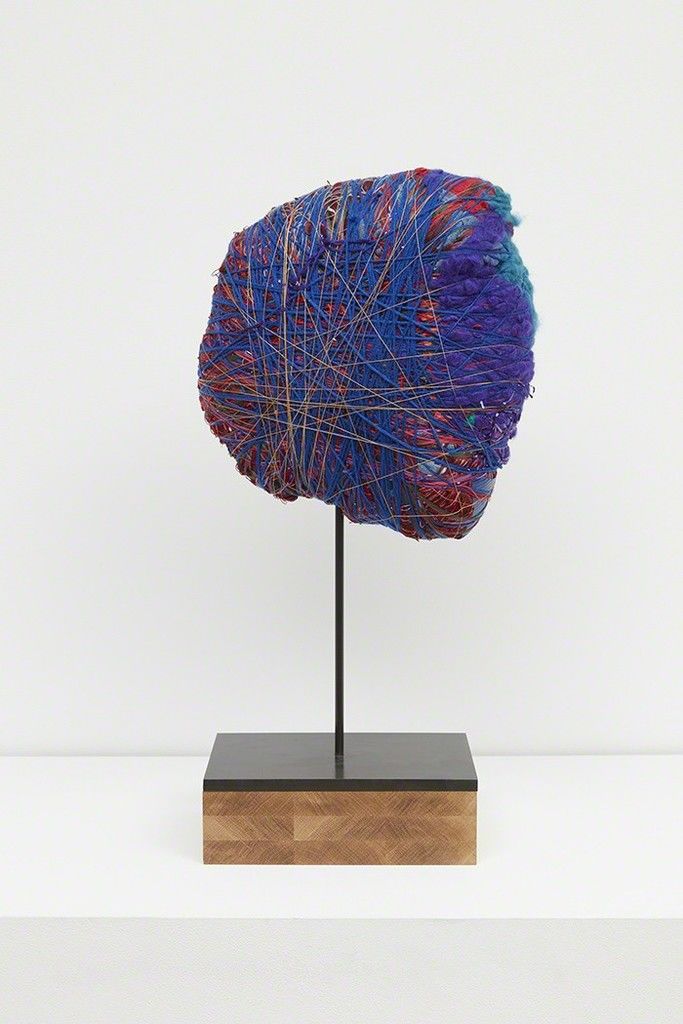

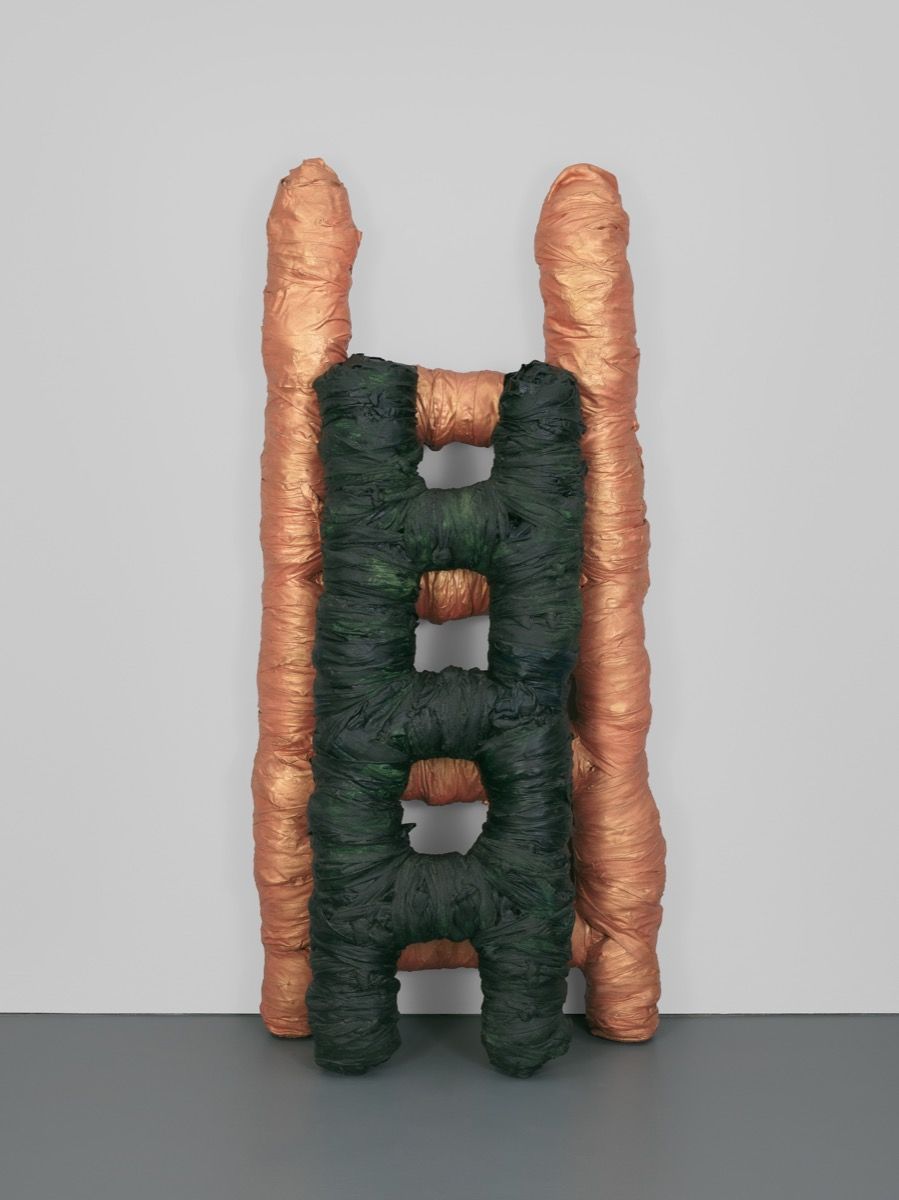

Paralleling this phenomenon has been an enthusiasm for fiber art. To a degree not seen since their brief moment of popularity in the late 1960s—coincident with the rise of the counterculture—artists like Sheila Hicks and Françoise Grossen have been garnering widespread acclaim. Porter followed up “Dirt on Delight” with her major project “Fiber: Sculpture 1960–Present,”which opened at the ICA Boston in 2014. In 2019, Anni Albers’s full-dress retrospective at Tate Modern was a surprise blockbuster; Frieze London devoted its new curated, thematic section to woven art; and the knitted sculptures of Ruth Asawa reached peak popularity: She was made into a Google Doodle.

Just as significant as this reappraisal of historical work is the success of contemporary artists working in craft disciplines: Arlene Shechet, Sterling Ruby, and Simone Leigh in ceramics; Diedrick Brackens in weaving; Jeffrey Gibson, who mixes Native American artisanal techniques with pop culture references. Even five years ago, such figures were not getting anything like the attention they have recently attracted.

These developments arguably culminated in major presentations currently on view at two important New York institutions. In a stunning gesture of cross-disciplinary parity, the newly expandedMuseum of Modern Art rehung its permanent collection with Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and…George E. Ohr. Though his name is probably unfamiliar to most visitors, they can easily see that the exquisitely furled forms of the so-called “Mad Potter of Biloxi” make an inspired juxtaposition with Van Gogh’s Starry Night (1889). MoMA also reopened with a temporary exhibition titled “Taking a Thread for a Walk,” which explores the institution’s little-known support for textiles in the mid-century era.

Meanwhile, down at the Whitney Museum, there is a whole floor devoted to craft. “Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019” casts a broad net over the museum’s permanent collection and comes up with a haul of interesting connections. There is Tawney, set alongside Agnes Martin , with whom she was strongly allied. The presence of figures like Richard Artschwager (who began his career as a furniture maker), Ree Morton , Alan Shields, and Harmony Hammond

attests to the breadth of craft’s relevance in the 1960s and ’70s—precisely the time when the studio movement sought to forge links and was left disappointed. The finale is Liza Lou’s extraordinary Kitchen (1991–96), completed after five years of painstaking beadwork, a testament if ever there was one to the power of craft.

Why does any of this matter? Lou’s work is a good place to start. It is explicitly in a feminist tradition, paying tribute to the domestic labor of generations of women. This could easily be didactic, but thanks to its sparkling materiality and jaw-dropping density, Kitchen communicates a nearly religious quality—a quality of wonder. And this, perhaps, gives us a clue as to why craft is finally having its moment. At a time when our collective attention is dangerously adrift, trapped in the freefall of our social-media feeds and snared in a pit of fake facts, handwork provides a firm anchor. It cannot be spun. It gives us something to believe in.

Craft matters, too, because it is the art world’s best path to diversity. There is a reason that Linda Nochlin never wrote an article called “Why Have There Been No Great Women Weavers?” There have been plenty. And potters. And jewelers. And metalsmiths. Craft is also a rich tapestry of ethnic diversity, having been practiced expertly by people of all nations and regions for millennia. You can make a strong case that the long-standing marginalization of the crafts—and the self-evidently crazy idea that painting isn’t one—was just the art world’s way of practicing sexism and racism, barely disguised as a policing of disciplines rather than people.

At long last, then, we have arrived at a reckoning. Art needs craft, and badly. So I have a suggestion. The next time you run into someone who wants to put craftspeople back on the sidelines—if, indeed, you can find anyone who still thinks that way—just think of Charlie Brown, and give them the reply they deserve: “Good grief!”